So ISAF has wound up its operation in Afghanistan and declared its objectives achieved after 4,500 military deaths, many times that in civilian deaths; billions of dollars worth of destruction and so on and so on. Predictably, the Taliban have also declared victory labeling the foreign intervention a failure.

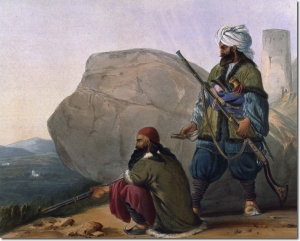

Just as predictably, commentators of all national origins and political stripes have tried to paint Afghanistan as some kind of black hole into which an army will march and never return. The British in 1839 – 42, (and another twice over) the Russians in the 1980s and now the Americans and British (again) in the 2000s.

I’m not so sure about ‘the graveyard of Empire’ label. Afghanistan highlights something systemic about foreign intervention there; failure of leadership, failure to plan, failure to understand the terrain (physical, cultural, psychological), failure to follow expert knowledge and advice. As cunning, brave, determined and atavistic as the Afghans need to be (and are) to defeat foreign adventures, we also like to ignore how the incompetence and arrogance of foreign militaries contribute to their own defeat.

As a Briton, the two most stunning examples have to be the first and last British contributions to this history.

The First Anglo Afghan War of 1839 – 42 was an unmitigated disaster. Sparked by the refusal to follow expert advice from specialists on the ground, who understood the Afghan ruler, Dost Muhamad, and what was going on in the country.

It followed the usual pattern: seemingly easy initial victories followed by the realization of backing the wrong man, poor leadership, confusion, defeat and humiliation.

A British army chaplain, the Reverand G.R. Gleig summed it up best when he wrote in 1843 that the First Anglo-Afghan War was

“begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity, [and] brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it.”

The Remnants of an Army. William Brydona, assistant surgeon in the British East India Company Army arrives at Jalalabad, 1842.

The campaign was a misbegotten mess from start to finish. To begin with, the war was unnecessary. Having decided to fight it, the British conducted the war in such a way as to make defeat the only possible outcome.

This gives an astonishing account of how it happened. This is a shorter appraisal, but equally eye opening.

***

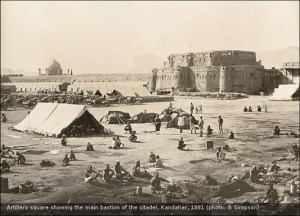

No luck second time around. British and allied forces at Kandahar after the 1880 Battle of Kandahar, during the Second Anglo-Afghan War.

Fast forward to the modern era and we can see a similar pattern, as this article in Foreign Policy makes clear.

The attacks on New York and Washington on the 11th September 2001 made action of some kind inevitable. I remember a die-hard liberal friend of mine (and near pacifist) asking ‘what else can they (the US) do?’ Which was a good question.

From the moment the US presence in Afghanistan arrived, they had no interest in nation building. No interest in attempting to solve the problems that had created the Taliban in the first place. They were only interested in driving out the Taliban and hunting down Al-Qaida. In fact, the ‘driving out the Taliban’ bit was outsourced to any Afghan force that would do the fighting.

The result was missed opportunities to round up the leadership of Al-Qaida and the Taliban holed up in the Tora Bora mountains.

This was compounded by a catastrophic misunderstanding of Pakistan. The US never properly got to grips with the fact that Pakistan was riding two horses at once. Taking US money and weapons to hunt down selected Al-Qaida leaders and personnel whilst quietly supporting the return of Taliban proxies to fight in Afghanistan. All the while giving safe haven to these proxies in Quetta and North Waziristan. And sheltering Osama Bin Laden.

Probably the worst blunder was allowing the return to power of the old Mujahedeen warlords who had sparked a vicious civil war, allowing for the creation of the Taliban and its spectacular military victories, in the early 1990s.

The Bush administration never properly tried to solve these problems and remained blissfully ignorant of Pakistan’s double game (as William Dalrymple’s review of Ahmed Rashid’s Descent into Chaos’ makes clear).

So when the new Obama administration recalibrated the US approach with the so called Af-Pak Strategy in 2009 / 10, it was already too late. The accumulated detritus of mistakes: corruption, neglect, ignorance and inaction had created a vortex that gained its own momentum.

There’s also the singular fact that Western militaries were geared toward fighting the wrong war. The Taliban insurgency was never the Soviet Army pouring into the plains of Germany. This analysis of the war against ISIS applies equally to Afghanistan.

Finally, the most remarkable account of military folly comes courtesy of the British once again. In a book review published in the London Review of Books, journalist and novelist James Meek describes something that can only be described as a disaster:

“The British army is back in Warminster and its other bases around the country. Its eight-year venture in southern Afghanistan is over. The extent of the military and political catastrophe it represents is hard to overstate. It was doomed to fail before it began, and fail it did, at a terrible cost in lives and money.

How bad was it? In a way it was worse than a defeat, because to be defeated, an army and its masters must understand the nature of the conflict they are fighting. Britain never did understand, and now we would rather not think about it.”

That gives a flavour of what the review is about.

Simply put, the British didn’t go to Afghanistan in 2001 and beyond to defeat the Taliban, restore order and create a nice place to live for Afghans. They went there for one reason: to impress the Americans.

Let me say that again. The British forces were in Afghanistan to impress the Americans. Everything they did was geared to showing the US that Britain could still cut it as a reliable partner and military power. That’s the British raison d’etre in Afghanistan. They had neither the money nor the manpower to do it, but that didn’t matter. Everything else flowed out of that.

British soldiers in Afghanistan, 2000s. At least the Army got out in one piece, but left it’s pride behind.

In terms of deaths, this disaster wasn’t as bloody (for the British at least) as the first round in 1839 – 42. In terms of treasure, it broke the bank; not least because Britain’s economy in the 2000s could buy considerably less than in the 19th Century.

It isn’t even as if they ever knew what was happening on the ground.

Putting British forces in Helmand province had no historical literacy. Meek’s article shows how the British were distrusted and hated from the start. And the British never understood why.

Meanwhile, Afghans couldn’t believe the British could be as stupid as they appeared; concocting an elaborate conspiracy theory to explain British incompetence. The 19th Century experience had left Afghans with a folk memory of the British as ingenious, cunning devils. A memory that failed to take into account what they saw in front of them.

”Helmandis believed deeply in the natural cunning of the British, so much so that the former chief (actual) Taliban commander in Helmand, the late Mullah Dadullah, was known as ‘the lame Englishman’ on account of his one leg and his extreme deviousness. For this reason people found it hard to account for Britain’s conduct in Helmand. There were two possibilities: the less likely was that the British were naive and ignorant. The favourite explanation, widely and sincerely believed, was that, secretly continuing to exercise imperial control over Pakistan, they were working hand in hand with the (actual) Taliban to punish Helmand, and that the Americans were trying to stop them.”

Whatever angle you look at it, this latest ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan signals another failure of leadership and knowledge. It does not suggest the invincibility of the Afghans in their mountain fastness. Afghan history is more complex than that.